View this blog as a PDF here. This is an updated version of our biennial report on the state and local tax systems. View the previous version of this report here.

Learn about who pays Texas taxes here.

A fair and adequate tax system would allow the state to invest in the building blocks of thriving communities — schools, health care, public safety, roads, and parks – that we all need, whether we are Black, brown, or white, and wherever we live in Texas. The type of tax system we need should provide enough revenue to maintain these public services and equitably divide up the responsibility for funding these services according to a household’s ability to pay. Unfortunately, our elected officials have chosen to give the wealthiest Texans and corporations a pass in contributing to state needs.

The comptroller estimates that Texas state taxes will generate $170 billion to support public services in the 2024-25 budget cycle. School property taxes could raise another $66 billion at the local level for public education during this period. But despite these large sums, Texas continues to rank near the bottom across the U.S. in investing in a prosperous future for our residents. The state’s low ranking in state and local taxes as a percentage of personal income (37th in 2020) leads to fewer resources to invest in public schools, health care, and other services.

Despite their dismal record of underinvestment in our future, current state leaders prioritize property tax cuts over our children. The governor has pledged “the largest property tax cut in Texas history” and the lieutenant governor has designated three property tax cut bills among his top priorities this session. Before enriching high-end homeowners and profitable corporations with another round of tax cuts, the Legislature should first pay its overdue bills.

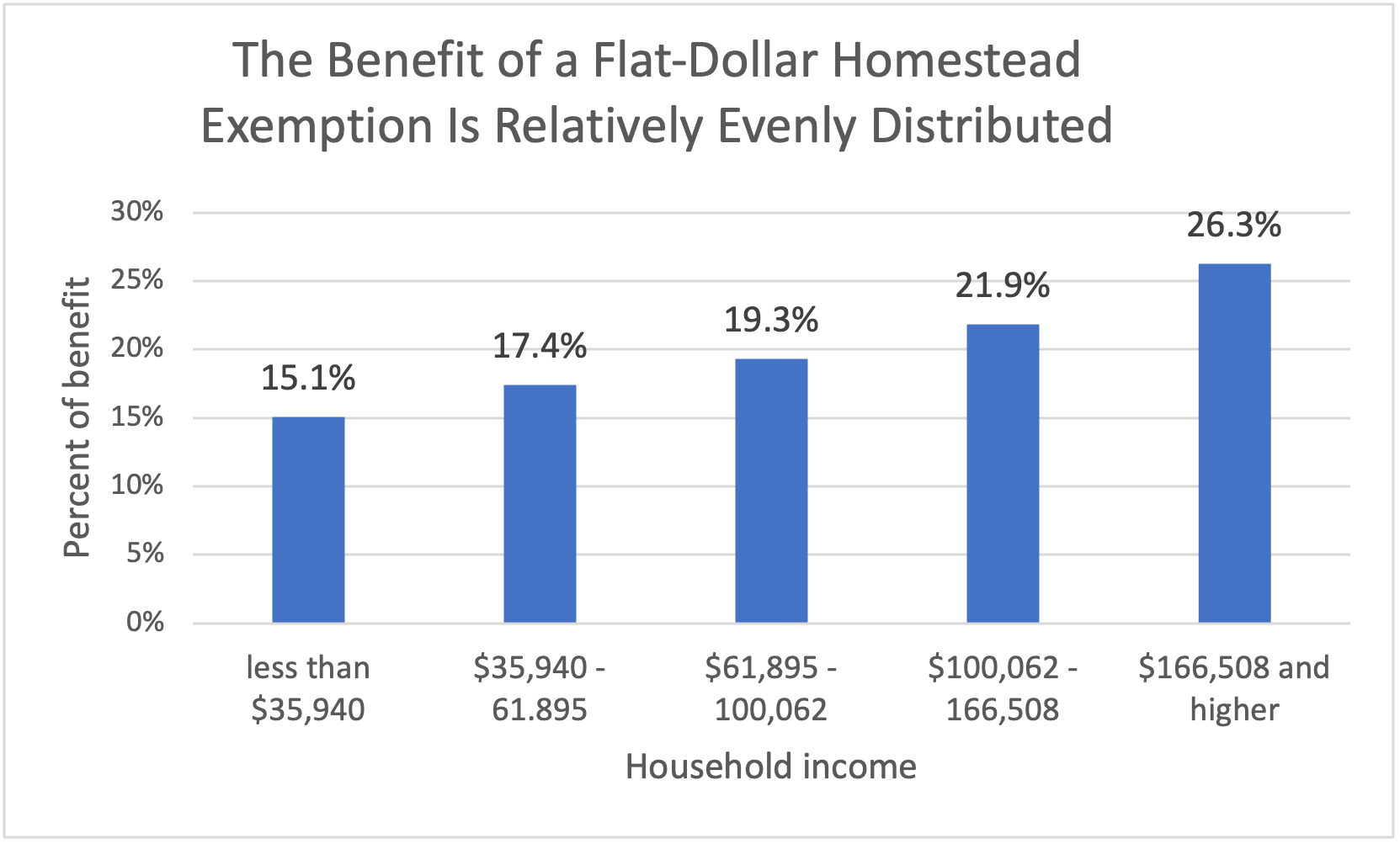

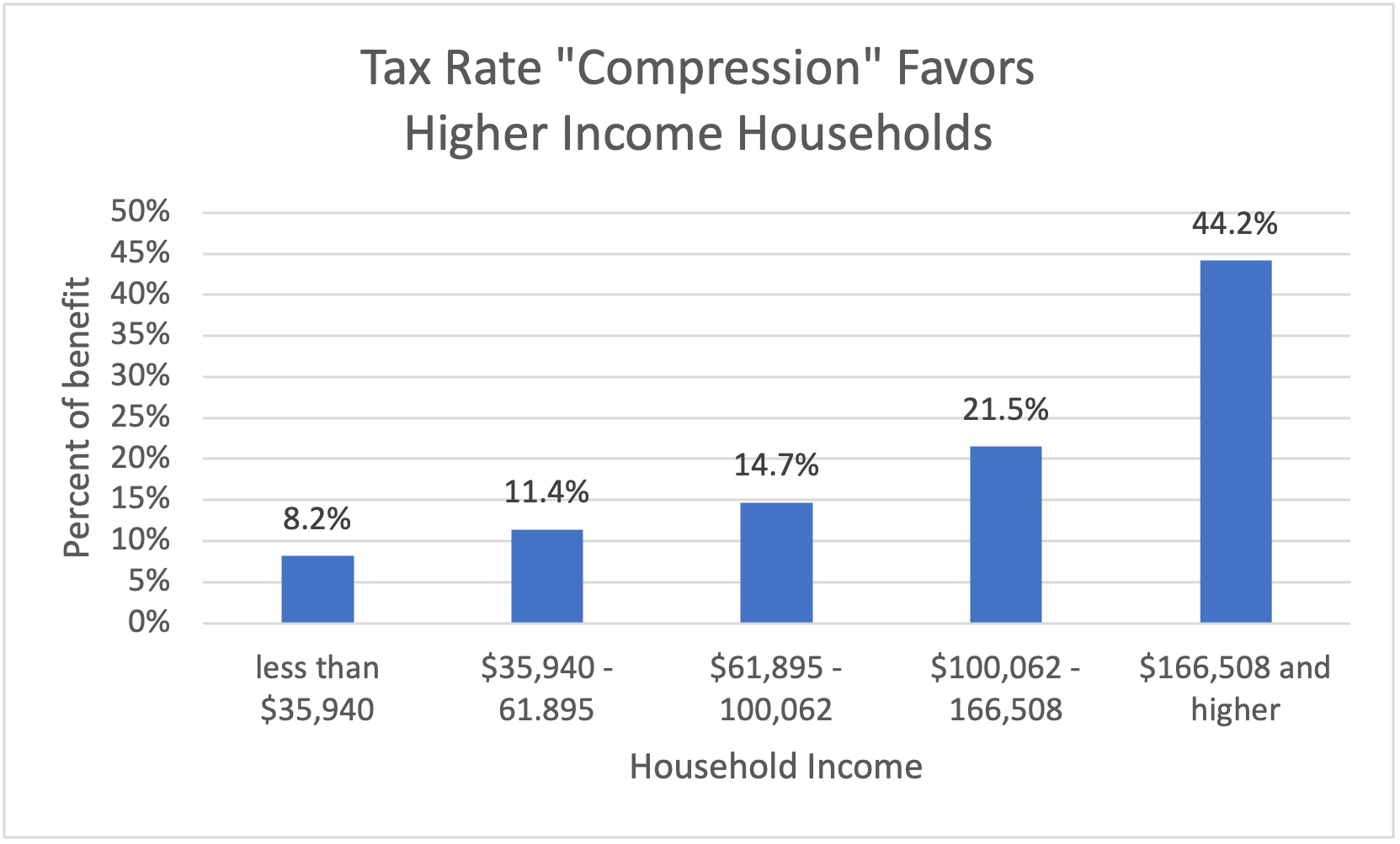

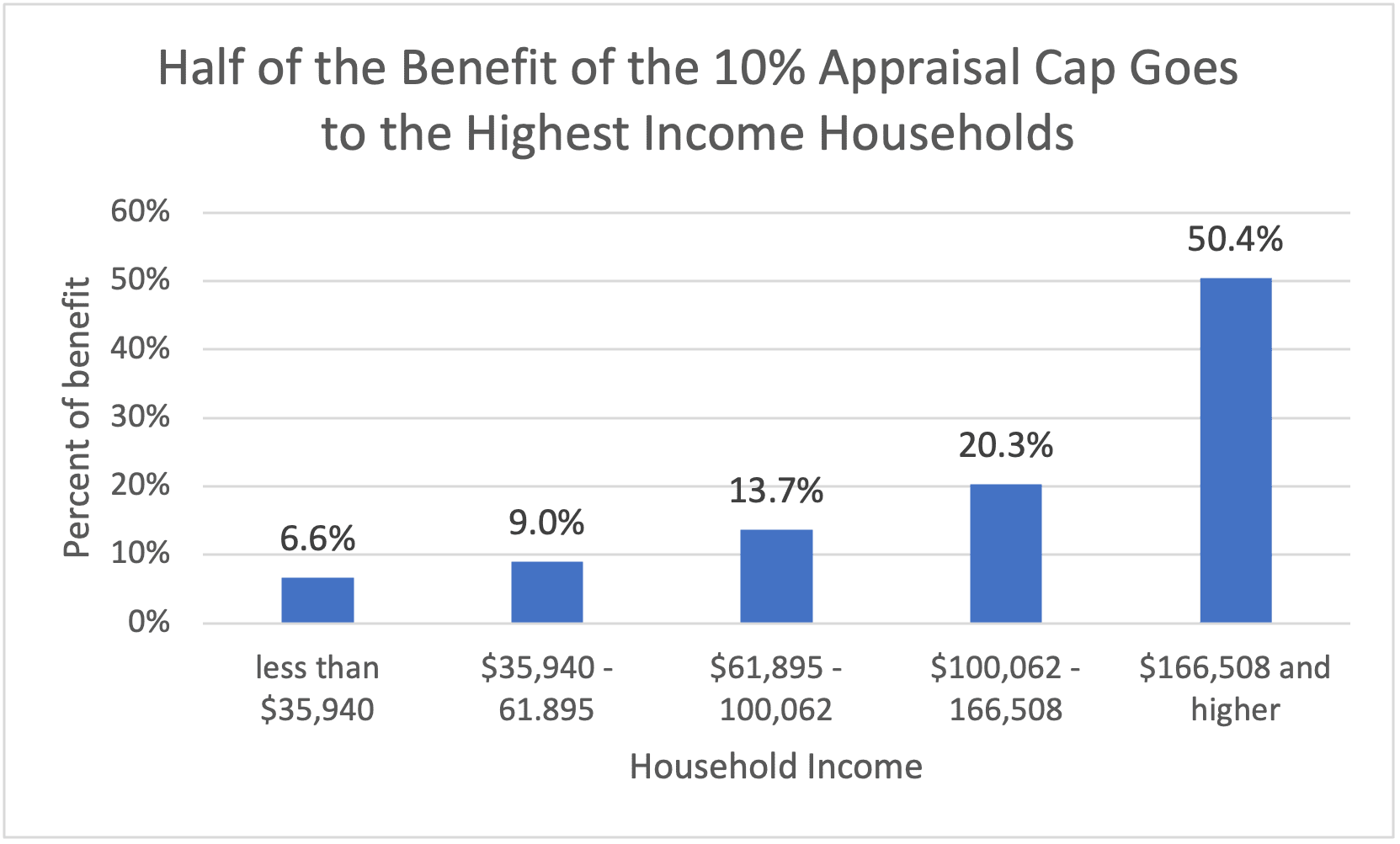

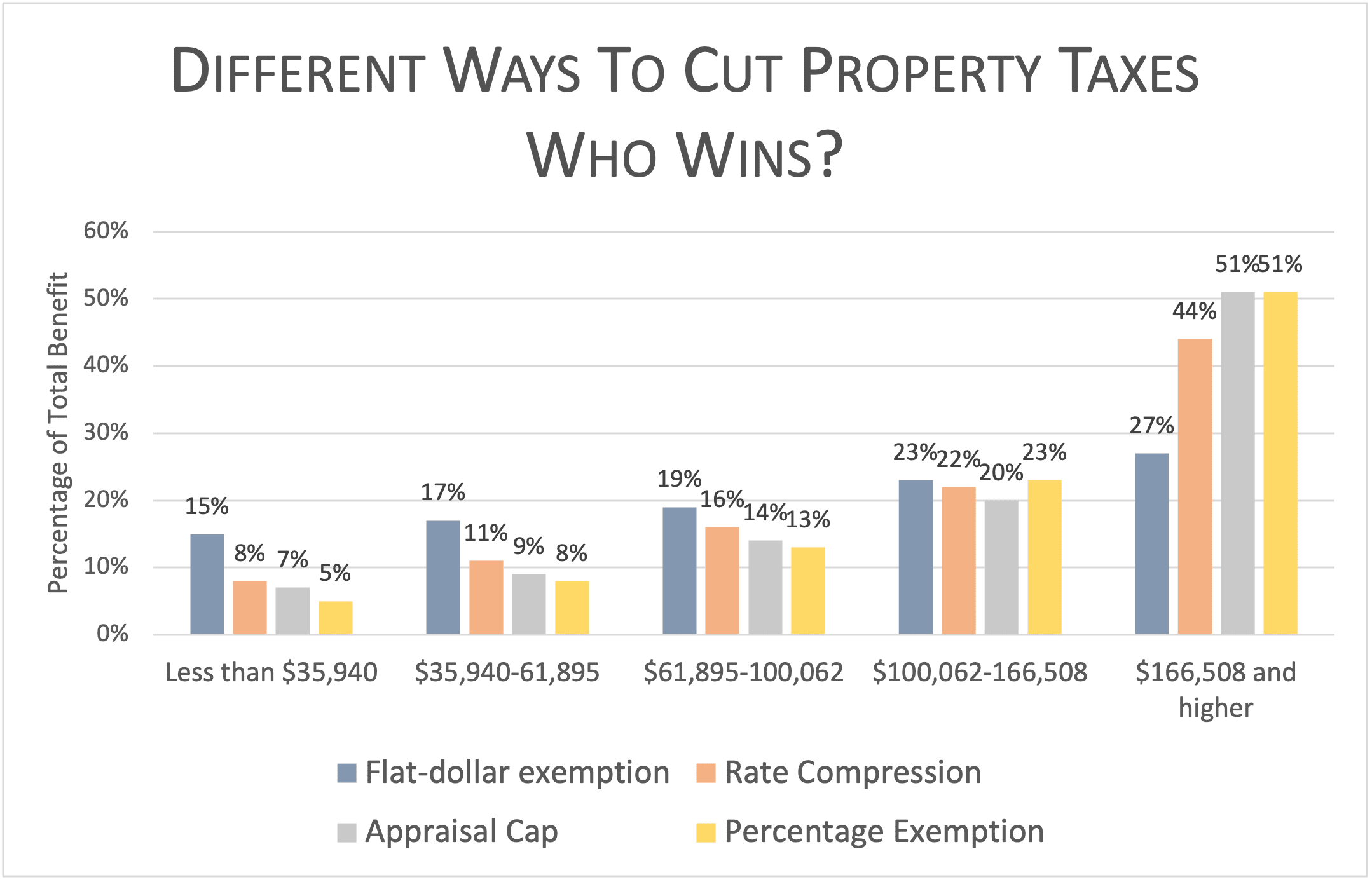

There are several different ways to cut property taxes, each with a different impact on Texas families with different incomes. This piece will examine four tax cut options and, using data from the comptroller’s Tax Exemption & Tax Incidence report, outline how low- and moderate-income families would fare compared to high-income families.

Homestead exemption from school property taxes

If you own a home in Texas, you pay property taxes — but not on the full value of your home. Appraisal districts estimate the market value of all homes, usually on a yearly basis. This is each home’s “appraised value.” The appraisal district then makes any applicable reductions for which that taxpayer qualifies, resulting in the “taxable value.” One type of reduction in the value subject to taxation is called a “homestead exemption.” The tax rate set by each local taxing authority — a school district, city, county, community college, hospital district, or other special district — is then applied against the taxable value to determine the property taxes owed.

School districts are currently required to give all homeowners a $40,000 exemption. This reduces the taxable value of all homes by the same dollar amount — $40,000, regardless of whether you live in a $150,000 or $900,000 home. In most school districts, this exemption reduces the school property taxes homeowners pay by about $400 a year per household.

You can see that the benefit of the homestead exemption is spread fairly evenly among all Texas households, with a greater share going to the income groups more likely to be homeowners.

Tax rate “compression”

The current school finance system, adopted in 2019, requires school districts to reduce their tax rate as local property values increase. The state could increase the amount by which tax rates are reduced (“compressed”) by increasing state spending to replace school property taxes in a revenue-neutral swap that would leave net local school revenue unchanged. An across-the-board rate cut would benefit businesses, which pay just over half of school property taxes. But considering the final incidence of property taxes, including actions by businesses to adjust to a rate cut by increasing profits, cutting prices, or increasing wages, the benefits would be significantly tilted toward higher-income families than lower-income families.

Appraisal caps

Under current law, the taxable value of a homestead cannot increase by more than 10% a year, even if its market (“appraised”) value has increased by more. Because higher-value homes have historically tended to appreciate in value faster than other homes, half of the benefit of the appraisal cap accrues to the one-fifth of Texas households with the highest income. A lower appraisal cap could exacerbate this imbalance.

Appraisal caps can lead to unequal treatment of similar homes. For example, assume a homeowner has stayed in a quickly appreciating house for decades so that its taxable value has been suppressed far below its true market value. A newcomer to the neighborhood buys a similar house across the street, but its appraisal is now set to its sale price, reflecting its market value. In that case, you get two homeowners with similar houses but with radically different appraisals and therefore radically different tax bills, favoring the long-term homeowner.

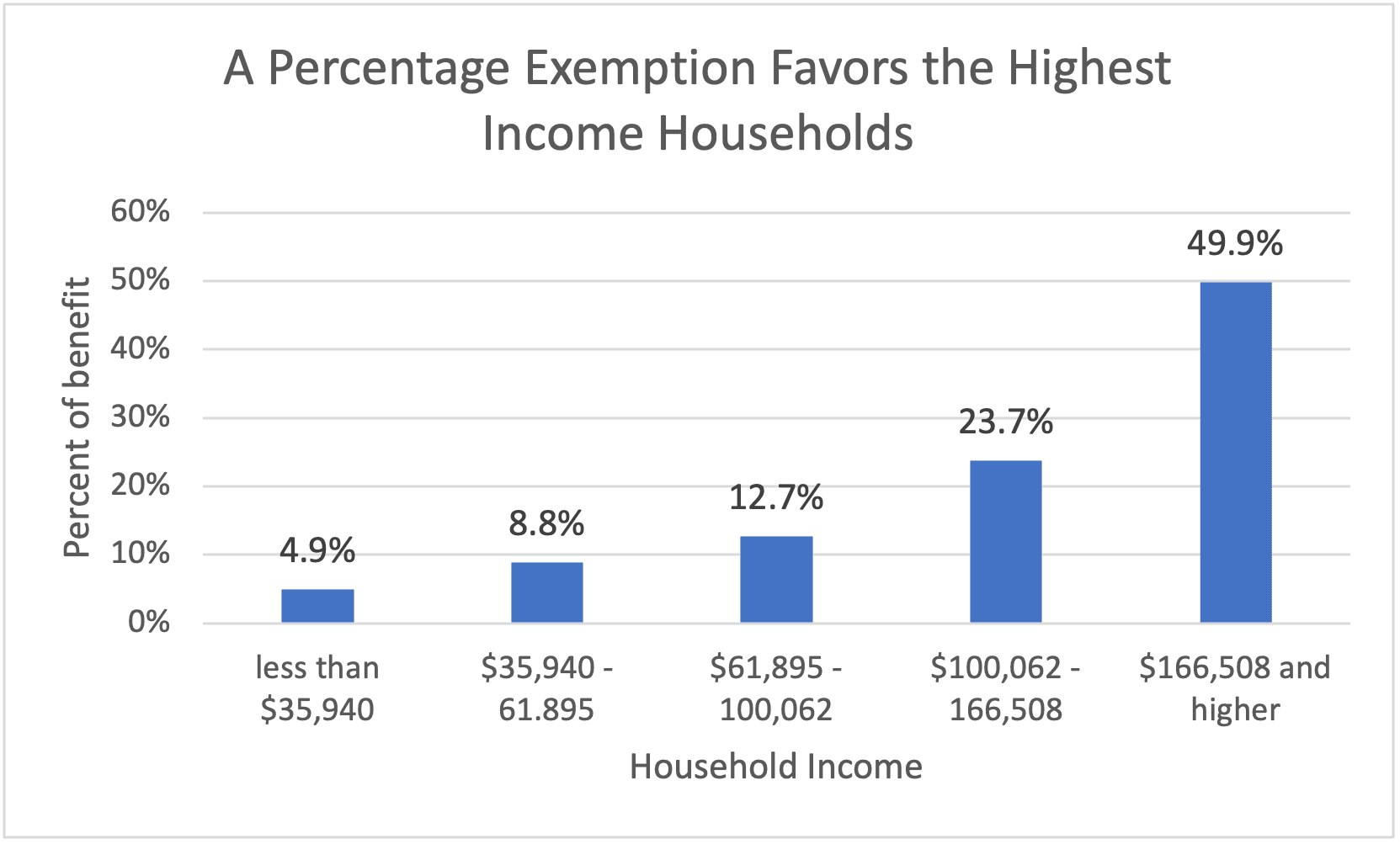

Percentage homestead exemption

In addition to the state-mandated $40,000 homestead exemption, school districts can exempt a percentage of the value of a homestead, up to 20%. In contrast to the flat-dollar exemption, which reduces the taxable value of all homesteads by the same dollar amount regardless of value, a percentage exemption gives the biggest break in dollars to the highest-value homes. This concentrates the benefits of a percentage exemption among the highest-income households, which own the highest-value homes.

Cities, counties, and other local taxing units are generally allowed to give only a percentage homestead exemption. Giving these elected bodies the option of granting a flat-dollar exemption would improve the equity of local property taxes.

Comparing the four ways to reduce property taxes

We can now examine side-by-side charts of the impact of these four alternative methods of reducing property taxes.

First, look at how each of the five income groups would share in the benefit of the alternatives. For four of the five income groups — the 80% of Texas households with annual incomes of less than $165,500 — the flat-dollar homestead exemption directs a larger share of the benefit to them than any other alternative. But for those households with the highest income — over $166,500 per year — appraisal caps and percentage exemptions give them the lion’s share of the benefit.

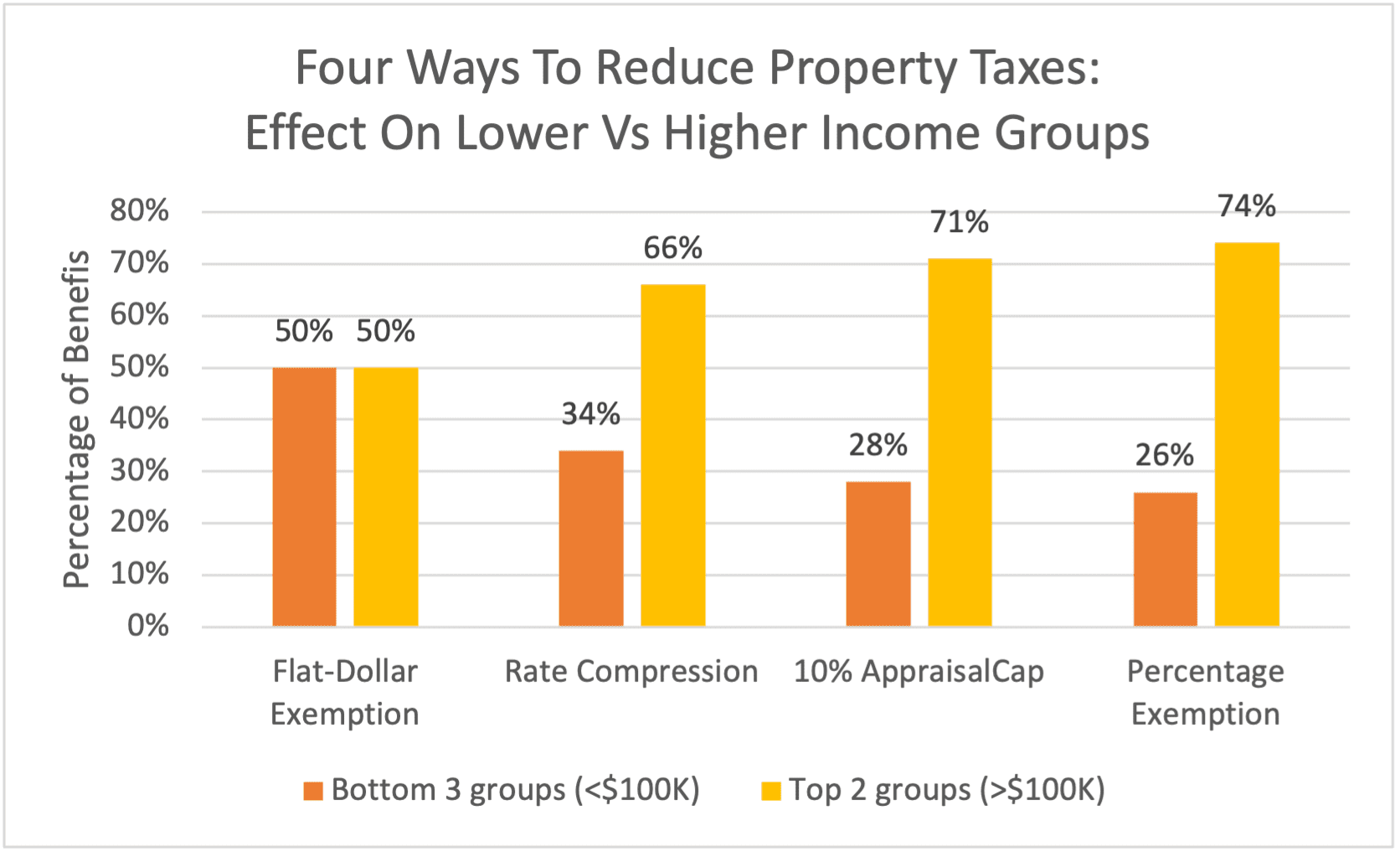

Another way to look at the effect of these alternatives is to consider how the benefits would be split between the households in the lower three income groups — those with incomes under $100,000 — compared to the share of benefits that would be received by those in the higher income groups — those with incomes over $100,000. This shows clearly that a flat-dollar exemption would divide the benefit the most evenly between these two sets of households, while the alternatives would direct from two-thirds to three-quarters of the benefits to the minority of households in the upper income brackets.

But before considering any of these alternatives, the Legislature should take advantage of the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity afforded by the state’s unusually large increase in available revenue to stop playing shell games with the hard-earned tax dollars of Texans and our families and start investing in the Texas we have long deserved. This session, lawmakers and budget writers should strategically use historic balances to support long-neglected state employees and services and make equally historic investments in the future of all Texans.