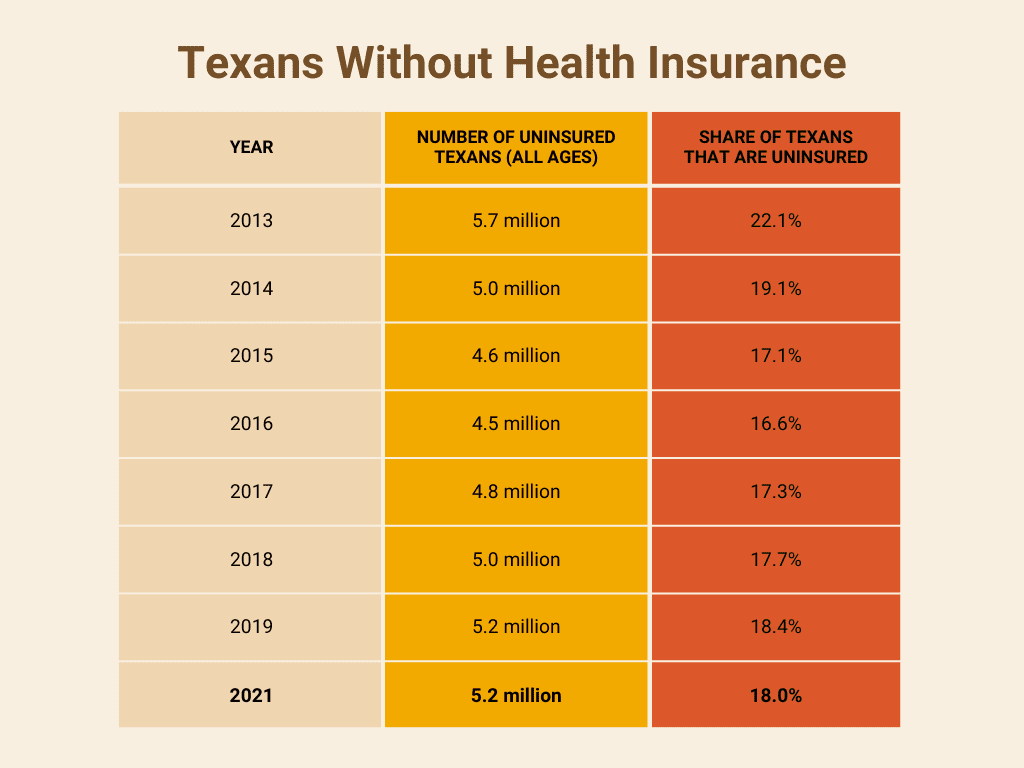

The U.S. Census released its newest estimates of uninsured Texans in 2021 in mid-September, which show very small improvements since 2019* in the percentage of uninsured Texans.

What Changed to Stall Texas’ Bad Trend of Increasing Uninsured Rates?

Because the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted Census operations in 2020, the Census is comparing 2021 results with 2019.

The number of uninsured Texans in 2021 was very close to the 2019 estimate, but how Texans got their coverage changed: the share of Texans covered through jobs shrank, while the share who bought coverage in the ACA Marketplace or enrolled in Medicaid increased.

These increases were largely driven by Congressional actions that (1) made the ACA Marketplace insurance far more affordable and (2) kept Medicaid beneficiaries covered throughout the Public Health Emergency (PHE). The PHE remains in place and is expected to continue until at least January 2023.

Texas in 2021: Worst for Both Children and Adults

- 5.2 million Texans (all ages) were uninsured in 2021, meaning 18.0% of Texans were uninsured.

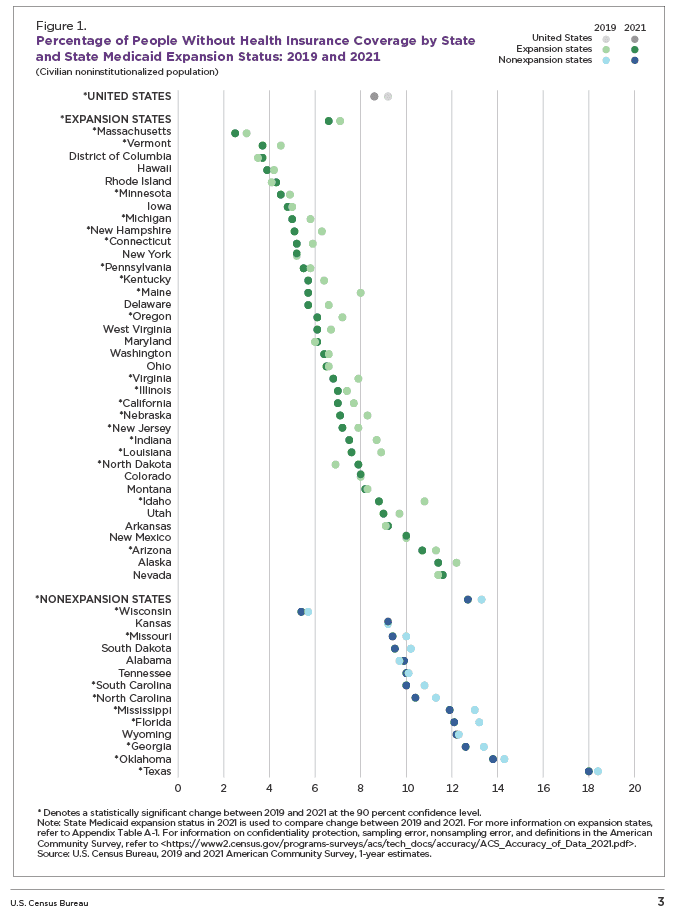

- Texas is the state with both the largest number and percentage of uninsured residents in the United States. Texans make up 9% of the U.S. population, but 19% of the country’s uninsured population.

- Texas has the worst uninsured rate by a big margin: Texas’ 18% uninsured rate is 4.2 percentage points worse than Oklahoma’s, the next-highest rate. The U.S. 2021 uninsured rate is 8.6%.

- Nearly 1 in 4 working-age Texans 19-64 is uninsured, making up the biggest share of Texas’ uninsured, with younger adults at the highest likelihood of being uninsured.

- Texas children and youth (under 19) are more than twice as likely as U.S. kids overall to be uninsured: 11.8%, compared to 5.4% for the U.S. Only one other state (WY) has a child uninsured rate in double digits. Texas’ last-place rank is despite our child uninsured rate improving from 12.7% in 2019.

- Nearly 930,000 Texas children were uninsured in 2021, and the Census estimates 495,000 of those had incomes below two times the Federal Poverty Income Level.

- A much larger share of Texans who identify as Hispanic are uninsured. The gaps in coverage rates among racial and ethnic groups are much smaller for Texas children than for adults, because public insurance from Medicaid and CHIP is available for lower-income children (but not for adults).

- 34% of Hispanic working-aged Texas adults (ages 19-64) are uninsured — more than three times the rate of non-Hispanic white working-age Texans (11%).

- 16% of Hispanic Texas children are uninsured, compared to 8% of non-Hispanic white children lacking coverage.

- Black working-age adults also have a much higher chance of being uninsured, at 18%.

- Asian-American children and Black children in Texas have uninsured rates near those of non-Hispanic whites: 7% for Asian children and 9% for Black children.

Texas Can Turn This Around

As Every Texan staff described in August testimony before the Texas House Select Committee on Health Reform, our state government has several powerful tools available that could end our last-place ranking.

- Accept billions in federal funds to provide Medicaid to “working but poor” adults—both parents and adults without any dependent kids at home. Texas is one of only 12 states without coverage for poor adults. As the U.S. Census graphic shows, even states with very high poverty have much lower uninsured rates than Texas if they adopted Medicaid Expansion: Arkansas 9.2%; Louisiana 7.6%; New Mexico 10.0%, West Virginia 6.1%. Experts estimate close to 1.4 million of Texas’ uninsured would qualify for coverage if we take this step.

- Remove barriers to enrollment/renewal of currently eligible individuals in Texas Medicaid. After estimates are applied to remove undocumented children (ineligible for either Medicaid or CHIP) from the Census statistics, it still appears that 350,000 or more uninsured Texas children qualify for Medicaid or CHIP but are not enrolled. In addition, COVID-19 policies since 2020 have retained over 850,000 Texas children improving our child uninsured rate; however, these coverage gains for children will be at risk at the end of the PHE. Texas’ Medicaid agency needs a clear directive from the state Legislature to both remove current barriers and adopt the strongest best practices to keep eligible children and adults covered when the PHE ends and ensure successful transfer to other coverage for those at higher incomes.

- Maintain our state’s record-breaking enrollment at HealthCare.gov. Texas is already poised to do so, as 2022 enrollment grew 42% in Texas — from 1.3 to 1.84 million — the largest increase in the nation. This progress was driven by more affordable coverage and big federal investments in enrollment assistance and marketing. Census stats suggest that at least 1.5 million of 5.2 million uninsured Texans are eligible for Marketplace subsidies, and even more robust marketing and assistance could drive an even better result in enrollment for 2023 coverage.

Remaining Challenges

Citizenship and Immigration status: 1.4 million out of 5 million uninsured Texans in 2021 were non-U.S. citizens — a mixture of both lawfully present and undocumented residents. Texas covers lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid and CHIP, but the anti-immigrant policies of the previous federal administration frightened many parents into withdrawing their children from coverage. Many undocumented parents still fear that enrolling even their U.S. citizen children in Medicaid or CHIP will prevent future lawful immigration and citizenship.

- To reduce the size of the non-citizen uninsured group, Texas must eliminate the barriers to covering lawfully present children and adults. This will require a strong state role in outreach and reassurance to get eligible lawfully present immigrant children enrolled, plus a change in Texas policy that today excludes nearly all lawfully present immigrant adults from Medicaid.

- Like other high-immigration states, Texas can — and should — pursue a comprehensive strategy to provide medical care to immigrants who lack lawful immigration status and are excluded from Medicaid, CHIP, and the Marketplace.

What’s Next: Our next blog on this topic will feature a more detailed look at how race and ethnicity, employment status, and family income and poverty affect health insurance coverage in Texas.

*The U.S. Census releases new uninsured statistics for the previous calendar year each September, based on its large American Community Survey (ACS, with a national sample size of 3.5 million). These statistics will be updated again in September 2023, with numbers that refer to 2022.