As of July 14, Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar projects a General Revenue (GR) balance of $27 billion when the 2022-2023 state budget cycle ends in August 2023. Many media outlets have reported the $27 billion as a “surplus” rather than a “balance.” But the terms are interchangeable only if you believe that Texas’ public PreK-12 schools and colleges, medical and mental health care, child protective services and foster care, community attendant care, college financial aid, and other services get anywhere near the state support they need and that the state budget fully covers inflation every two years. Neither is true.

For example, raising the Basic Allotment for schools by $1,000 sounds like a lot, but that’s what would have been required to keep up with three years of inflation since the last legislative increase in 2019. Ever since the 2019-20 school year, the Basic Allotment has been stuck at $6,160; if state law had pegged it to inflation, schools would have received almost $4 billion in additional state aid.

But back to that $27 billion GR balance. It’s the result of adding together state revenue already in the Treasury when fiscal 2022 started (including roughly $5 billion in General Revenue and $6 billion that piled up over decades, unspent, in General Revenue-dedicated accounts), plus taxes and other revenue the comptroller expects will be collected in 2022 and 2023, then subtracting the GR appropriated by the legislature to date. Last week’s $27 billion revised forecast is $15 billion higher than what was predicted back in November 2021. Half of that $15 billion improvement is due to how much better the sales tax is expected to perform, compared to last fall’s conservative estimate. Most of that is happening in the first year (2022) of the two-year budget, “fueled by inflation and rebounding economic activity after the end of pandemic restrictions,” the comptroller notes. Specifically, instead of the 3.3% inflation that was predicted last fall for fiscal 2022, this July revision has the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increasing by 7.6%. Lower inflation (4.4%) in 2023 will slow the growth in sales tax in the budget year that starts on September 1.

Hegar also said the Economic Stabilization (“rainy day”) Fund balance will be $13.7 billion after this fall’s transfer of oil and natural gas severance taxes, up from his prior forecast of $12.6 billion. Driving that increase is much-higher assumptions about crude oil prices: $90 per barrel in fiscal 2022 and $97 in 2023, compared to last November’s $75 and $70 estimates. Natural gas price forecasts are also up significantly in this current revision.

Unfortunately, it is not feasible to conclude that both the 2022-23 and 2024-25 budgets are on solid ground, or that future state lawmakers have a true “surplus,” if that’s defined as “way more than enough to meet the needs of a very rapidly growing state.” While this first year of the budget will end with $16 billion in unused General Revenue “in the bank,” the second year is much more uncertain, given recent inflation and other factors that the comptroller identifies:

The revised estimate is subject to substantial uncertainty. High inflation is now being met by the Federal Reserve System and other central banks with the intent of curbing price pressures by slowing economic activity in the U.S. and abroad. There is a significant risk that the shift to restrictive monetary policy may push economies into recession. Economic activity could also be impaired by further dislocations stemming from geopolitical conflict or renewed COVID restrictions among our global trading partners. While this is not a recession forecast and continued economic growth is expected, the rate of economic growth is anticipated to slow and revenue growth in fiscal 2023 is estimated conservatively in view of the degree of uncertainty and heightened risk of recession.

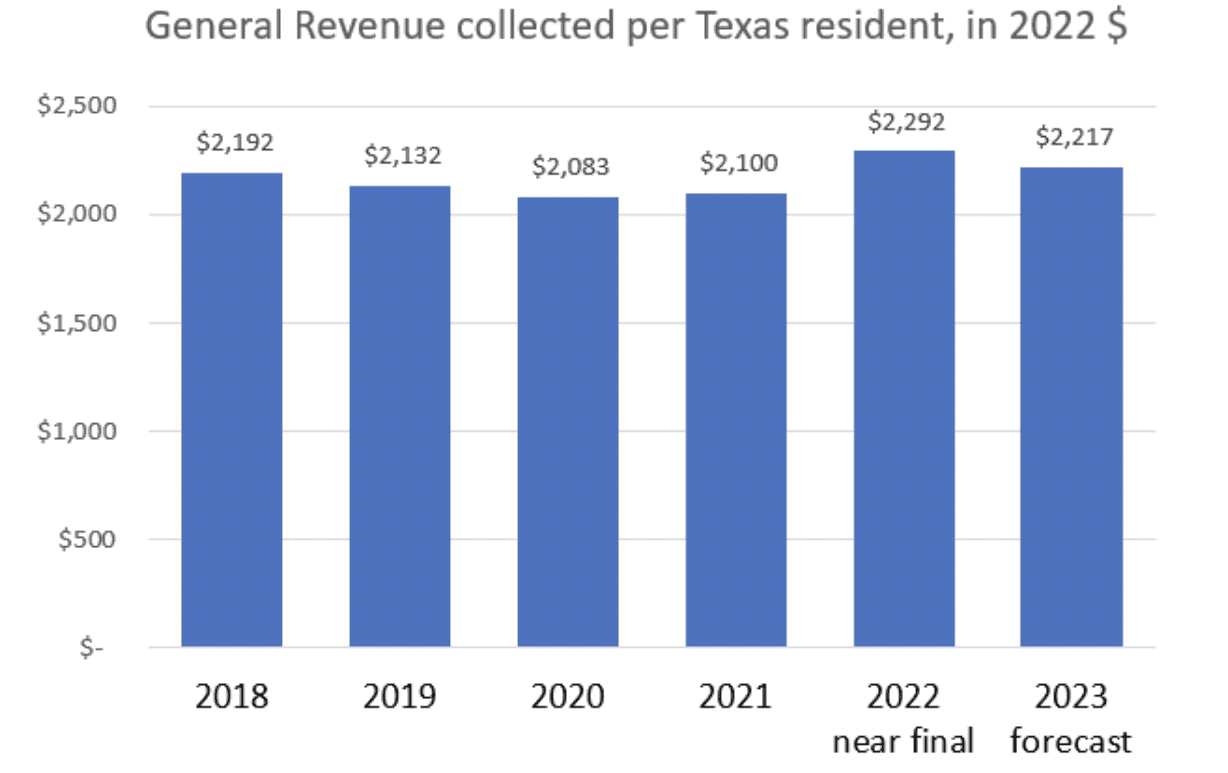

Because of the uncertainty, the comptroller is only forecasting a 2.6% increase in 2023 revenue, compared to this year’s estimated growth of almost 25%. Looking only at actual net General Revenue brought in during the year, and adjusting for the forecast’s population and CPI inflation, the July revision shows a return to the revenue levels seen back in 2018 by 2023. (To be clear: the chart excludes the significant “cushion” provided by long-standing General Revenue-Dedicated balances but does account for constitutional transfers to the “rainy day” and Highway Funds.)

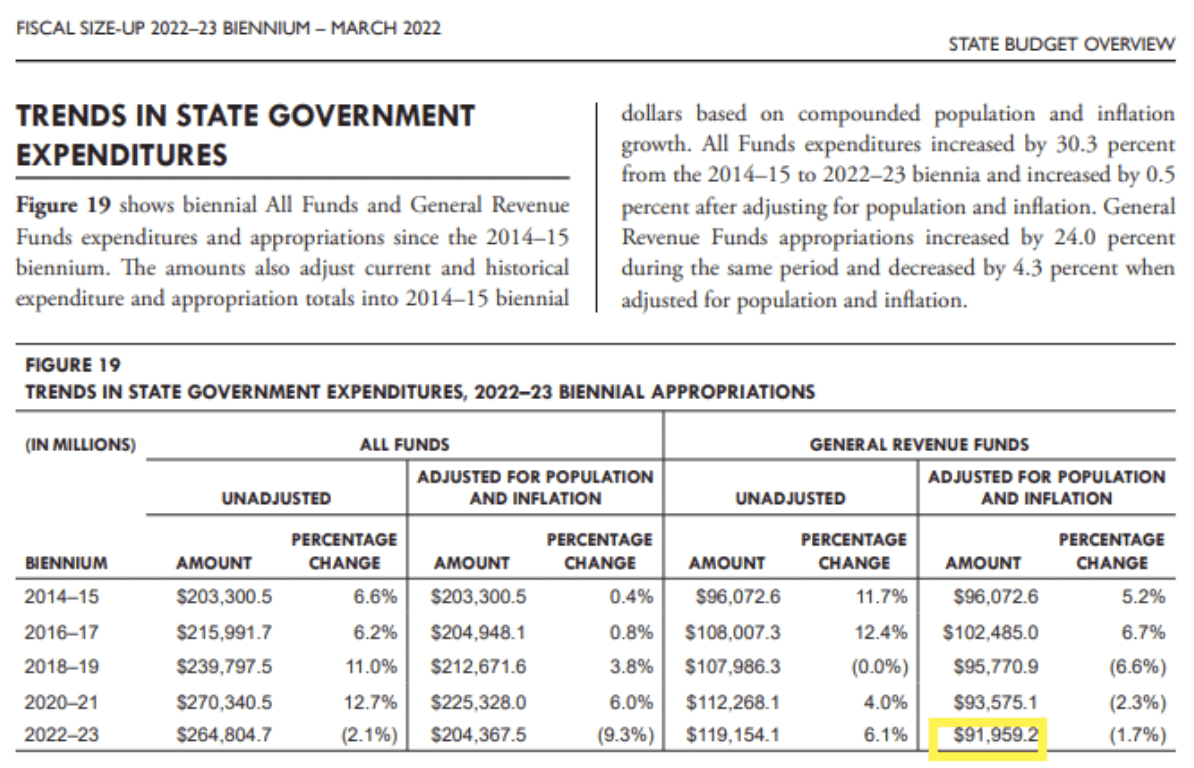

Meanwhile, General Revenue appropriations to date have fallen to their lowest real levels in more than a decade. Even before the recent spike in inflation, the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) had estimated that this two-year General Revenue budget was the third in a row not to keep pace with population and inflation growth.

Furthermore, once you know how the 2020-2021 budget went from a $4.6 billion shortfall in July 2020 to an $11.2 billion ending balance, it’s difficult to conclude that the state’s revenue system is really in better shape than ever, or reliable enough to take on more and more of what’s currently being covered by local property taxes, as some state officials are proposing. The hard truth is that the 2020-21 budget went from being in the red to having billions left unspent due to:

- $710 million in General Revenue reductions made to state services, primarily higher education, after leadership called for 5% interim cuts;

- $1.2 billion in first-round federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding that supplanted General Revenue in school finance formulas;

- $4 billion in federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) funds that replaced General Revenue previously budgeted for state workers, primarily prison guards and other correctional staff. This $4 billion Coronavirus Relief-General Revenue “swap” is what state budget writers approved when the 2021 regular session was drawing to a close; subsequent “swaps,” including those for Operation Lone Star in January and April 2022, pushed that total up to $5.9 billion, according to the governor’s office at the July 11 Senate Finance hearing.

Another $5.9 billion patch on the 2020-2021 Texas budget came from long-standing “smoke and mirrors” that counts some unspent but legally dedicated state revenue as if it were truly available for any general revenue budget purpose. One legislative budget writer referred to this as “not a healthy accounting practice” at a July 12 House Appropriations hearing, and asked Legislative Budget Board staff to recommend ways to further reduce the reliance on GR-Dedicated balances and bring “regular” General Revenue spending into true balance.

Looking forward to the final costs of the 2022-23 budget, Hegar has not yet factored some unpaid bills into the “balance” forecasts. For instance, Medicaid health care services may end up needing $2 to $3 billion in additional General Revenue, because anticipated medical cost inflation is another factor that legislative budget writers didn’t pay for in the 2021 sessions. Unanticipated inflation such as unusually high gasoline and electric utility costs may also require state agencies to receive more General Revenue. Prison health care and wildfire or hurricane damage are also big-ticket items that usually get dealt with in a supplemental spending bill.

Helping to reduce the General Revenue cost of supplemental appropriations are state budget assumptions about local school property tax increases that turn out to be too conservative. For example, the current estimate has local school property taxes coming in $1.4 billion higher for 2022 compared to last November’s estimate, which means the state doesn’t have to put an equivalent amount into the school formulas.

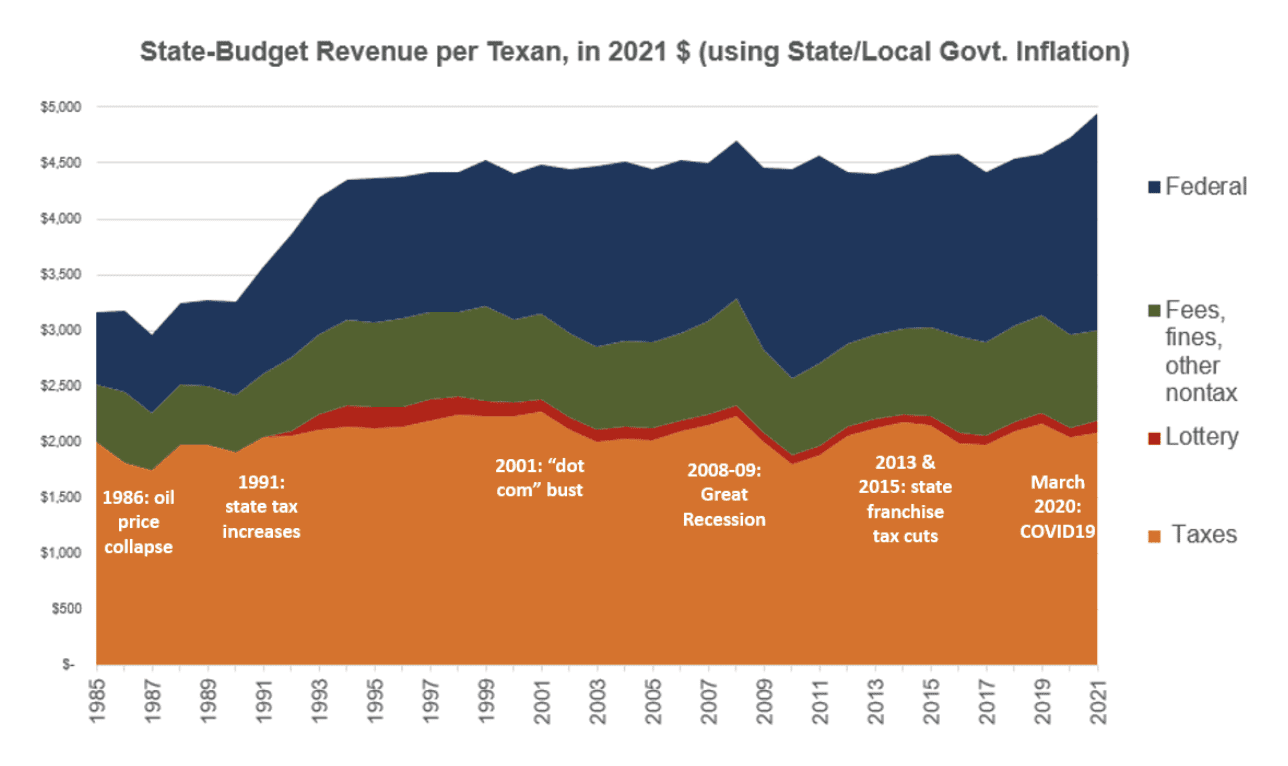

The July 2022 improved forecast suggests that a one-time use of General Revenue for a retired teacher cost of living adjustment should rank high on legislators’ budget priorities, after ensuring that state support for PreK-12 and higher education at least keeps up with inflation. But Texas simply can’t keep taking on ongoing responsibilities without finding new and sustainable ways to pay for them. A longer-term look at Texas’ non-federal revenue sources makes it clear that the state budget often fails to keep up with population and inflation. Any new responsibility––whether it’s the 2019 session’s $6 billion and climbing school finance tax compression changes, or 2022-2023’s use of at least $4 billion for Operation Lone Star––only stretches existing state support to a dangerously thin level.

As for the Economic Stabilization Fund (ESF): in theory, it provides an almost $14 billion “cushion” in case the economy unexpectedly and drastically worsens, and state lawmakers find themselves far short of the General Revenue needed to continue existing state services. But recent legislative changes to the ESF require it to have a “sufficient balance” that, by law, is set at 7% of General Revenue appropriations. If the balance falls below that, oil and natural gas tax transfers to the State Highway Fund are suspended until the ESF is sufficiently replenished. For 2022-2023, the sufficient balance is $8.3 billion, leaving only $5.4 billion (about 4% of 2022-23 GR spending) that can be tapped before affecting highway funding.

While the state budget outlook has improved enough for legislative budget writers to deal with stagnating state aid for schools, and to consider one-time, long-overdue items such as a retired teacher pension increase, the true condition of the Texas budget is still being masked by one-time federal aid, interim cuts to higher education, smoke and mirrors, and unpaid bills. Unless new revenue sources are explored, continuing to prioritize border spending and new tax cuts for wealthy homeowners and corporations will endanger all of our access to public schools, college, health care, and other state services in the long run.