From El Paso to Houston and everywhere in between, Texans are entitled to affordable and nutritious food to ensure our families live long and healthy lives. However, even in 2023, Texans in both cities and rural communities are grappling with the issue of food insecurity. With over 3.7 million Texans experiencing food insecurity, officials in power must prioritize policies that promote a Texas where nobody has to go hungry and everyone can prosper.

Community members and nonprofit organizations dedicated to food equity have proposed various solutions to make access to food more equitable and accessible. Expanding SNAP benefits, increasing benefit amounts, and addressing unemployment, among other measures, are all effective ways to directly reduce food insecurity. But many Texans face systemic and physical barriers that make grocery shopping difficult. To ensure equitable access to food and resources, legislators need to take a holistic approach to overcome these physical barriers.

Although food insecurity and transportation seem like separate issues with distinct solutions, city planners and community members must work together to develop more equitable solutions by recognizing and addressing these problems as part of a highly flawed, broader system. Those who do not live within walking distance of a grocery store and don’t have access to a car can find it extremely difficult to get food on the table. This problem is particularly prevalent in rural and lower-income urban areas, where grocery stores may be few and far between. In these communities, residents may count on public transportation as their only avenue for providing food for their families. Our state’s lack of funding and development of public transit proves that these problems are system-wide. Food insecurity is no longer just a matter of access to food — it’s inextricably linked to inequitable transportation and urban development as well.

Looking at Houston

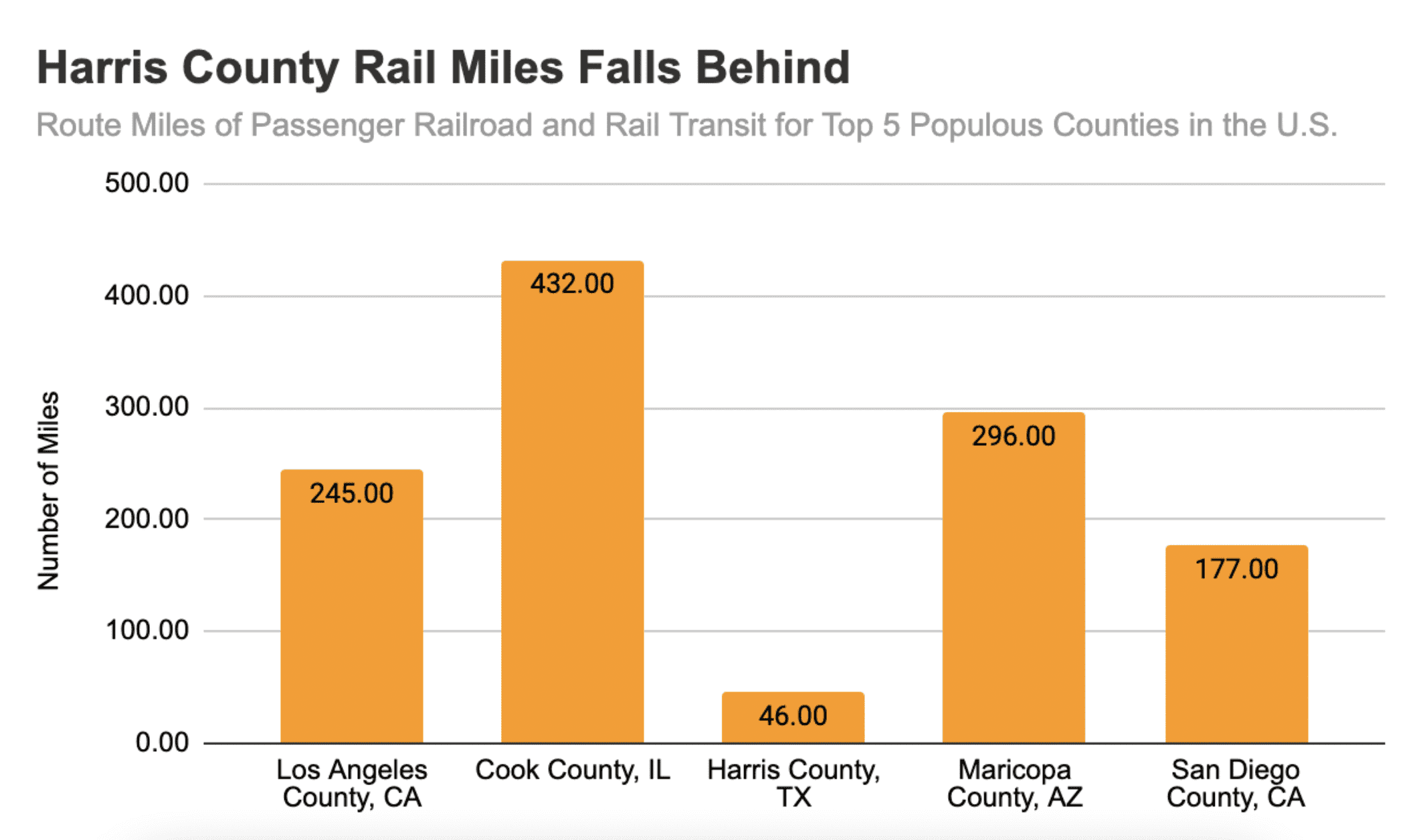

The city of Houston is a prime example of the relationship between food insecurity and a lack of public transit. Among the 23 North American cities ranked by the Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index, Houston ranked 22nd regarding sustainable public mobility of residents. With a population of over 2.3 million, Houston is the most populated city in Texas and the fourth largest in the country. Although Houston has a robust economy, acclaimed academic institutions, and a world-class medical center, its inadequate transportation system poses a barrier to access to food. Despite being home to the third most populous county in the nation, Harris County, Houston’s miles of rail transportation are falling far behind compared to other populated counties. Such low miles of transit available for ridership set a scene for millions of people left without the option to travel without depending on a car. Multimodal transportation is essential to the people of any city for countless reasons, but it especially explains why so many Houstonians find themselves stranded in food deserts with no accessible means of escape.

Some of Houston’s downtown core has seen dramatic economic revitalization since the 1980s, yet most of the city’s historically underdeveloped neighborhoods in the north and east have increased in poverty by comparison. These underdeveloped areas of the city — made up predominantly of communities of color — have highly restricted access to grocery stores and force community members to venture miles away from their neighborhoods to obtain groceries. According to a Rice University study, over 500,000 Houstonians live in USDA-designated food deserts.

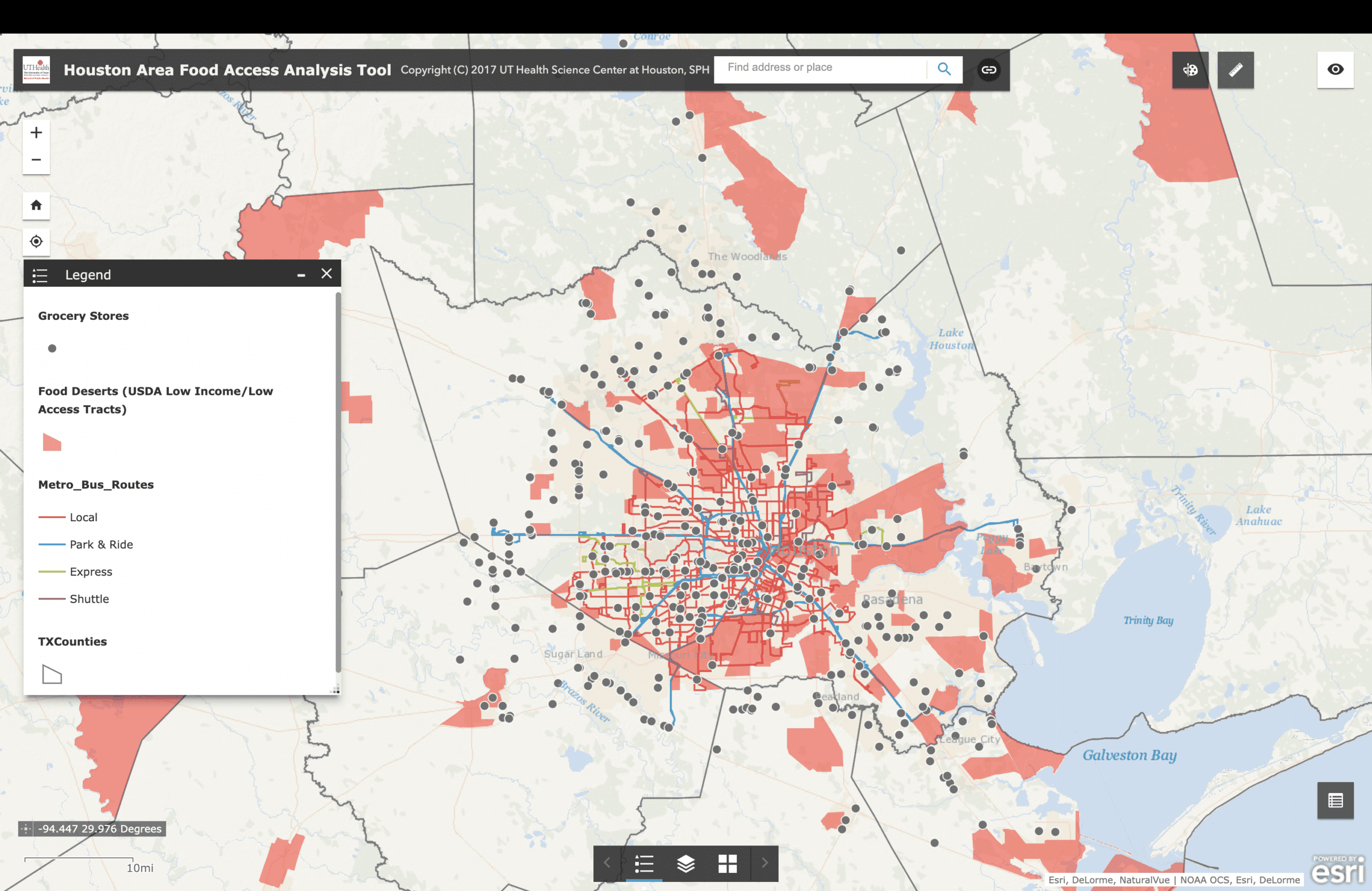

The Food Access Analysis map by the University of Texas Health Science Center shows that Houston’s food deserts are located in the historically underserved communities on the north and east sides of the city. By overlaying Houston Metro bus routes with the large swaths of the city marked as food deserts, we can visualize the difficulty of mobility in the communities that receive little to no service from the city’s transportation system, like Aldine in the north and Dyersdale in the northeast. The map shows the lack of development of public transit infrastructure in some notable neighborhoods like Aldine in the north and Dyersdale in the northeast of the city.

The map also provides the number of grocery stores within each Houston zip code. According to these numbers and 2021 Census data on the median income for households in each zip code, patterns arise that point to systemic inequities with tangible consequences. Of the ten zip codes in Houston with the highest median income, earnings ranged from $72,762 to $102,440. Not a single one of these areas had any food deserts within its boundaries — they had an average of 4.8 grocery stores within or on their boundaries. By comparison, in the ten zip codes in Houston with the lowest median income, earnings ranged from $22,434 to $26,141. Of these zip codes, eight were partially or totally considered a food desert. On average, these zip codes have only 2.3 grocery stores within or on their boundaries — half the average number of grocery stores that the wealthiest zip codes contain. Every Texan, regardless of income or earnings, deserves access to grocery stores and the ability to obtain food and ingredients from a multitude of sources. Food security is a right, not a privilege.

As a result of this infrastructural neglect, residents have a considerably difficult time just getting to grocery stores. For example, residents of Dyersdale who have virtually no Metro bus lines to use would have to walk almost an hour to get to the nearest grocery store without a vehicle. This exclusionary approach to urban and rural development effectively “road blocks” lower-income families that cannot afford a car, further restricting them from getting groceries even with aid from the government via programs like SNAP.

Equitable Solutions

- Provide community-based food sources: Food pantries, produce gardens, and vendor markets are all critical tools in the fight to prevent food insecurity in our state. In addition to promoting local economies, they also reduce the heavy dependence on retail grocery giants.

- The Dallas People’s Gardens provides diversity and resiliency to the food supply chain by empowering local communities to participate in local food production.

- Invest in multimodal transportation: To combat food insecurity, state leaders must provide transportation to healthy food sources outside communities for residents who cannot get groceries within their neighborhoods. People without cars can travel outside their communities more easily if they have safe and sustainable multimodal transportation options, like biking, walking, and public transportation.

- The Grocery Bus line in Austin connects low-income Latinx communities that often lack adequate transportation options to grocery stores.

- Adapt public transit for people who need it the most: The best way to make transit more equitable is to tailor it to the lifestyle of those who need it the most. Second or third-shift workers, people with disabilities, those living in rural areas, and those who need to access resources outside their communities must have access to an efficient and effective public transportation system.

- A transit service is provided by CARTS (Capital Area Rural Transportation System) in several rural counties around Austin, including Blanco, Burnet, Caldwell, Fayette, Hays, Lee, Williamson, and Bastrop.

- Make public transportation more affordable: As part of their transportation budgets, local governments should experiment with free or subsidized services, such as ridesharing, metro/bus rides, and commuter trains, especially in places where public transportation isn’t available or is difficult to access. The Bureau of Labor Statistics cites that most Americans spend almost 16% of their typical annual budget on transportation costs. When the cost of commuting to stores is reduced or eliminated, lower-income families will be less financially stressed and can better provide for their children.

- Riders with a Reduced Fare ID (RFID) Card in Austin can receive a half-price fare. This service is available to seniors 65 and older, Medicare card holders, active military personnel, and people with disabilities.

- Shift to moving people instead of moving cars: Increasing car mobility by any means necessary has been one of the primary objectives of urban developers for decades. This car-centric thinking led to a proclivity to build massive highways and engineer cities to accommodate the flow of cars, resulting in divided communities and the exclusion of lower-income neighborhoods from adequate resources.

- The Highways to Boulevards Project proposes replacing aging highways with assets like streets, housing, and green spaces to repair, rebuild, and reknit communities. In addition to being places for local businesses and public interaction, these streets better integrate with transportation systems.

There should be no privilege in having affordable access to healthy foods — food security is a fundamental human right. With the increasing number of people calling Texas their home, the fight against food insecurity requires a holistic approach to ensure everyone has access to the food and resources they need to succeed. Texans should not experience difficulty getting to a grocery store due to poor maintenance of transportation infrastructure that prioritizes cars over people. Community members must be engaged in the planning process to develop solutions that will benefit all Texans, regardless of class, age, ability, or location. In order to provide resources to disenfranchised communities and fight off food insecurity, Texas leaders must ensure that multimodal transportation methods are effective and within the reach of every Texan.