The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas recently released “Skipping School,” the second in its three-part series looking at the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Texans aged 16 to 24. Authors Anna Crocket and Jason Saving use enrollment data from 2016 to 2021 to show a decline for 16- to 24-year-old Texans enrolled in college either full- or part-time. Crocket and Saving do not provide an answer to the near 5% drop in high school enrollment from 2020 to 2021 but, even without a clear explanation for high school-aged Texans, the reduced attendance at the high school and college levels will have ripple effects in the years to come. Texas needs good, common-sense policy solutions now to mitigate the impact, and attacking ethnic studies programs is not the answer.

“Skipping School” shows how nearly a decade of work to increase student enrollment in Texas colleges and universities was dismantled in the years leading up to the pandemic. The threat this poses to the state’s long-term economic productivity is concerning and, as policy analysts, our job is to sound the alarm. The task falls on educators and education policymakers to “look up” and heed the warnings.

Teachers are burning out faster than a paper match dipped in AquaNet. Students are protesting to demand safer classroom conditions. Communities are fed up with their schools being used as tools for political gamesmanship.

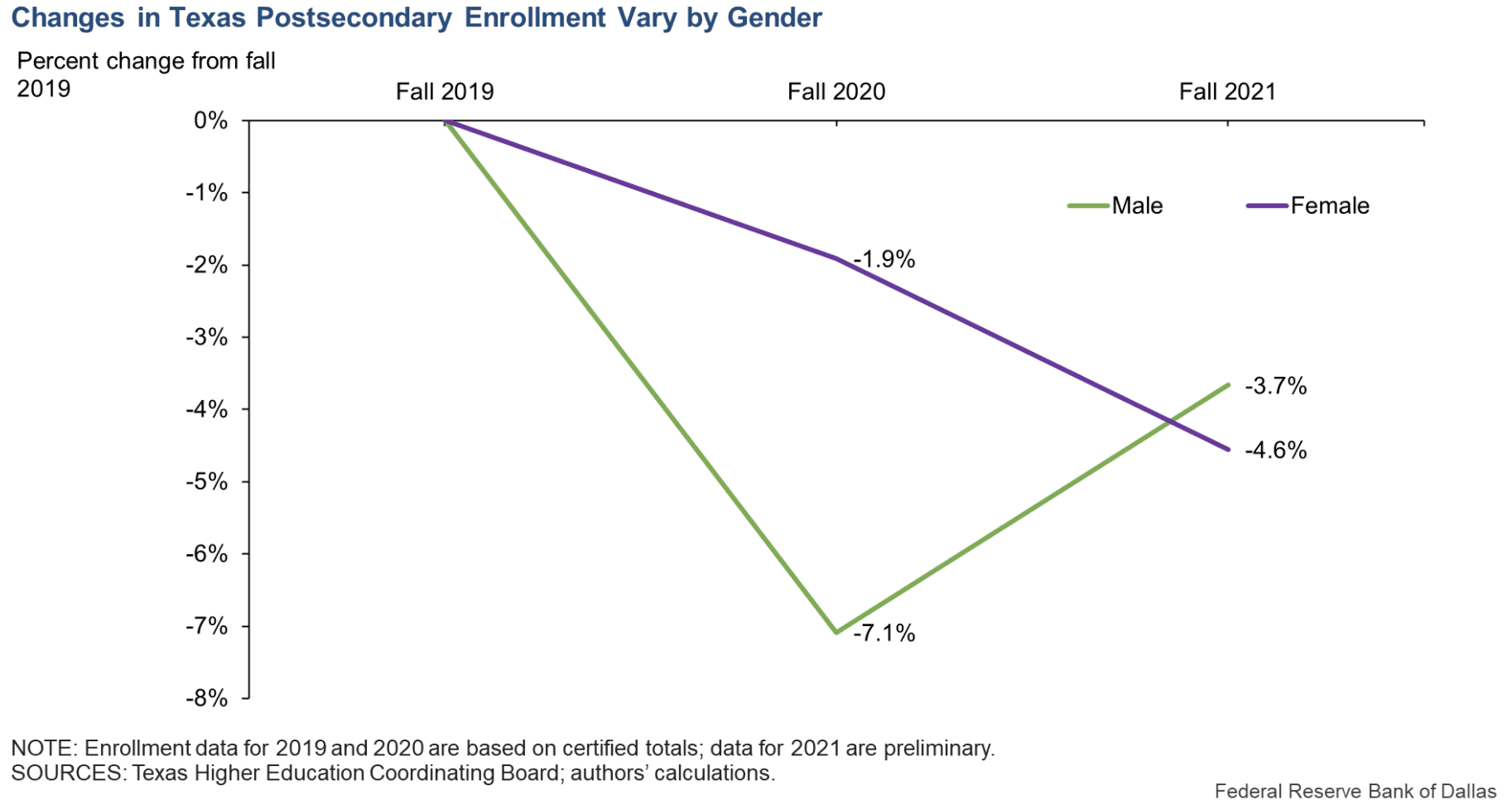

The effects of the pandemic on student enrollment are disproportionate for female, Black, Latino, and Asian students. While male students halfway recovered in Fall 2021 from a near 8% drop in enrollment in Fall 2020, female Texans continued their downward decline in enrollment, going from a 1.9% decrease in 2020 to a 4.6% decrease in 2021.

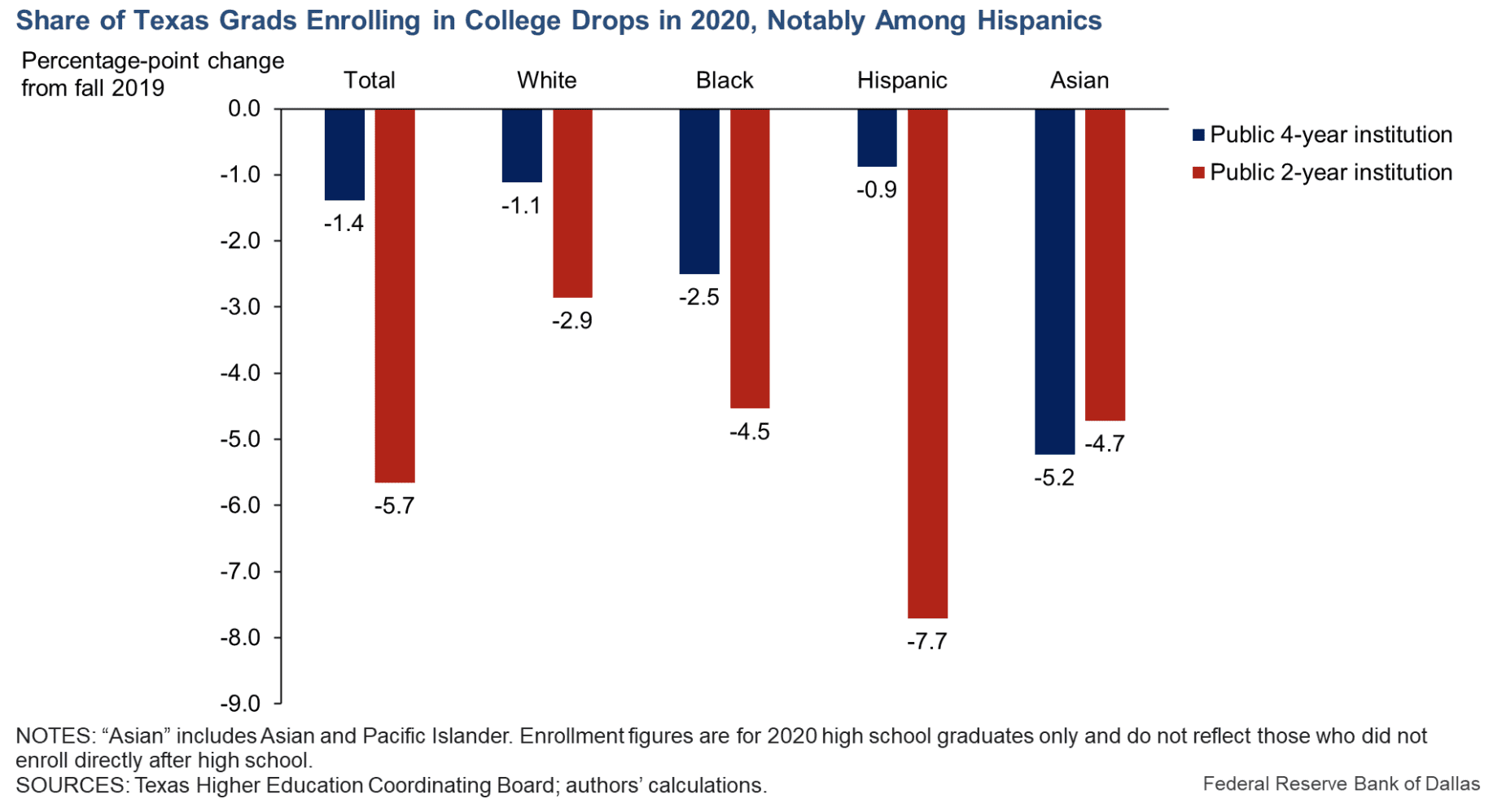

Black and Asian students saw a decline in four-year college enrollment compared to the statewide average. While Texas saw an overall 1.4% decrease in four-year college enrollment, Black Texan enrollment fell by 2.5% and Asian Texan enrollment fell by 5.2%. For two-year college enrollments, only Latino Texans, at 7.7%, outpaced the overall decline of 5.7%. Black and Asian Texans saw their enrollments drop by 4.5% and 4.7%, respectively.

Ethnic studies programs help reduce student attrition and promote intellectual curiosity among students, teachers, and parents alike. According to a recent report, ethnic studies, especially when taught by teachers trained in the field, “prime student awareness of the many structural social hurdles they face.” Equipping ninth graders with the tools of ethnic studies also has the lingering effect of solidifying gains made in high school, which students often carry into their college experience. Culturally relevant education and meeting students where they are provide significant gains in student attendance, grade point average, and overall credits earned.

Now is the time to lean into ethnic studies as a solution to several systemic issues that undoubtedly contribute to the reduced enrollment outlined by Crocket and Saving. Texas is going in the wrong direction if we want to reach the proposed goal of having 60% of Texans ages 25-34 earn a certificate or degree by 2030. The current animosity aimed at school administrators, teachers, and students exacerbates the feelings of despair across our state’s public school system. If Texas wants to keep its economy strong, policymakers must find a way to address the declining student enrollment shown in the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’s report. The first step is to abandon ongoing attacks on books and curriculum, and the second is to embrace the power and benefits of ethnic studies.